Troops at Camp Heidelager

Nazi Germany’s Lesser Known SS Military Complex and Death Camp

Part One: History

Hidden in a wilderness region of southwest Poland is the Blizna Historical Park, a memorial museum dedicated to the preservation of one of Hitler’s top-secret projects. It is difficult to imagine that in this lovely and heavily forested area was once the largest SS training camp outside of Germany. Few foreign visitors even know about its existence, but a visit provides a unique step back into history to learn of the horrors suffered by the prisoners and the local Polish population at the hands of the Nazis.

On my first visit in 2016 to my grandfather’s village in Niwiska, I was astounded that any major atrocities could have happened so close to my grandfather’s birth home. A massive model of a V-2 missile rests ominously in the center of the park. A rocket such as this had been launched and sometimes crashed hundreds of times over my Polish family’s home, just a fifteen-minute walk through the woods!

At the outset of WWII, the Germans had been well acquainted with every square mile of Poland as the Austria-Hungarian Empire encompassed this territory for over 150 years during the era of the Great Partitions from 1772 to 1918 when Poland ceased to be a nation. Set in this wilderness area of southeastern Poland, Blizna and the surrounding villages provided a secluded area for the very worst of the Nazi’s military forces: the SS or Schutzstaffel.

The SS was founded in 1925 to serve as bodyguards for Adolf Hitler. By WWII, it had evolved into the most powerful and feared organizations in all of Nazi Germany. Recruits had to prove none of their ancestors were Jewish and received elite military training. The SS had more than a quarter million members engaged in activities ranging from intelligence operations to controlling the Nazi concentration camps.

Setting up military training centers began almost immediately after Germany’s takeover of Poland in September 1939. The Supreme Command of the Armed Forces of the Reich (OKW) issued an order on December 21, 1939, to build the SS training base on the area of the former counties of Debica, Mielec, and Kolbuszowa. Important transportation routes (railways and roads) and industrial facilities such as chemical and tire plants, the aerospace plant in Mielec, and numerous sawmills made an ideal location for Camp Debica, later renamed as SS Heidelager.

Entrance to the plant near Pustkow

The main task of Camp Heidelager was the training of collaborationist military units and for the reorganization of branches that supplemented the units’ losses. The Estonian SS legion and the Ukrainian Division “Galizien” were created in Pustków.

A concentration camp was created by prison and forced labor in Pustkow. It is estimated that about 15,000 prisoners were killed or murdered at these camps: 7,500 Jews, 5,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and 2,500 Poles. The camp originally opened on June 2, 1940, with the arrival of the first forced laborers, mostly Jews and Belgian prisoners. The conditions were so terrible that most prisoners did not survive the first few months.

The second major group was Soviet prisoners who arrived in October 1941. In the beginning, the POW camp was no more than an enclosed area, and prisoners received minimal or no food and were reduced to eating grass and roots. There were no barracks, so prisoners had to sleep out in the open. A third camp for Polish forced prisoners was established in September 1942, and the conditions were no better than those at the first two camps.

In order to build this massive camp, most of the Polish villagers were displaced from their homes by mid-1940 and often had no more than two days to evacuate. The Germans took no responsibility for finding any housing resources for these people. It was the sad destiny for many to wander to a family member’s village outside the camp area in the hope a relative would take pity on them. Many of their houses were torched for new building projects, or some salvageable parts might be moved to build barracks for worker’s settlements. Displaced families were paid a meager compensation and porridge and black coffee was provided once a week.

Everyone above the age of sixteen was required to register and be accountable for their work serving the Reich. Without their land to farm or a trade to pursue, these Poles were forced to accept work at the camp for building projects. Many of their younger people were captured in group roundups and taken to Germany to work on farms or factories.

These local villagers were employed in the construction of the training ground to build railroads, concrete roads, sewage and water systems, and barracks. A large number of prisoners and workers from the Baudienst (the agency that registered and assigned the local villagers) were assigned for agricultural and horticultural work, and in workshops, warehouse, and in cleaning and food services. Large farms were established to ensure the proper amount of food for the crew and the troops staying at the training ground.

Captain Albrecht, a man of incredible evil and one of the characters in my novel.

The Germans used pre-war factory buildings and manor and housing estates consisting of thirteen large, two-family villas and several blocks of flats. The more stately homes were taken over as housing for the officers, and the more impressive buildings were used as SS headquarters. For example, the city hall in Kolbuszowa became the Gestapo Headquarters, and the Hupka manor house in Niwiska was taken over as housing for Colonel Ludwik Heiss.

A Villa at Heidelager

The camp included most of the features of a typical German town with entertainment, cultural, and recreational facilities for their soldiers. There was a cinema-theater that could accommodate over 2,500 people, a newspaper (“Der Rufer”), sports fields, large dining halls, and barracks. For officers, there were impressive villas and ranges for hunting parties.

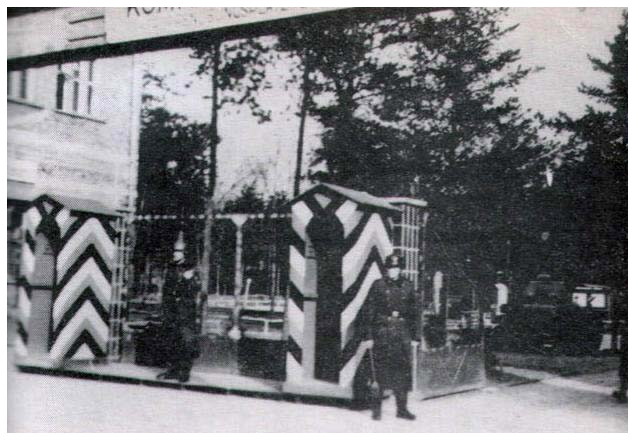

Entrance to Camp Heidelager

Camp Heidelager was open every Sunday for civilians who visited soldiers staying at the training camp. The guests and soldiers enjoyed facilities such as sports fields for recreation. Visitors often brought food and alcohol. They also brought news from the front that had a negative effect on the morale of the soldiers, and there were often desertions.

There was also a brothel that was located in the forest far from the rings and barracks called “Waldkaffe” (Forest Cafe). The entire area of this place was fenced and included a guard who kept order and a cook from the camp.

One bizarre feature of Camp Heidelager was a small fake village. The empty houses were painted, clothes were hung permanently on a clothesline, and statues of farm animals graced the farm. The purpose of this small village is not known, but the locals and foresters found it puzzling.

In the summer of 1943, Hitler moved his top-secret V-1 and V-2 missile research program to Blizna located near the center of the camp. The project had been centered in Peenemunde, Germany but Allied bombing almost destroyed the program. With that devastation, the Germans thought it was more prudent to divide the program between three different regions. The first launch of V-2 rockets took place in Blizna on November 5, 1943, and the V-1 missiles launches began in the spring of 1944. Hundreds of missiles were launched, but many failed, leaving huge craters along their paths.

The Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa or AK) had the entire area under surveillance and performed heroic acts of sabotage and numerous raids on the missile program. The local foresters, railway workers, and farmers risked their lives on missions to covertly obtain exploded missile fragments that were then smuggled to the Allies.

Once the Germans saw the war was turning in the Allies’ favor, they began to move equipment, prisoners, and anything of value to Germany and torched the wooden structures to erase proof of their actions and atrocities.

The activity at Camp Heidelager came to an abrupt end when the Russians moved into the area in early August 1944.

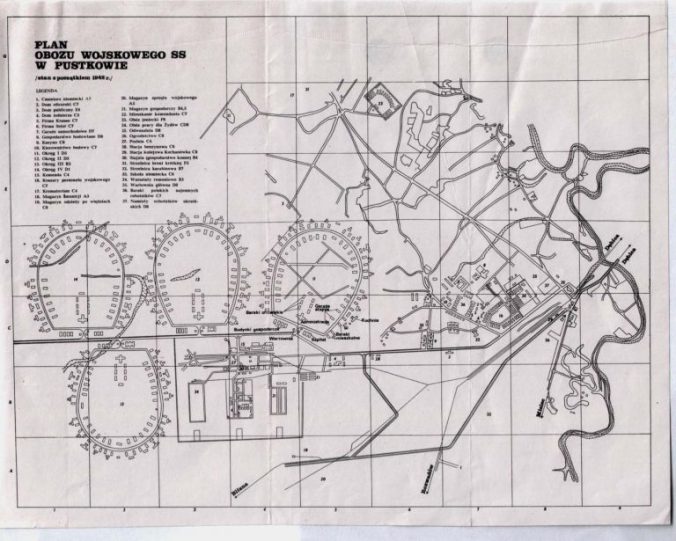

Map of the rings and barracks in Camp Heidelager near Pustkow

Himmler on a visit to Camp Heidelager in 1943.

*(Part One of Three Articles)

Next: My 2016 and 2018 Visit to Blizna Historical Park

I have just completed “War in the Wilderness,” a historical novel set in WWII in Camp Heidelager. The story is based on the true events and real people who lived under Nazi Germany’s Rule of Terror. I will notify you when the actual publication date is assigned!