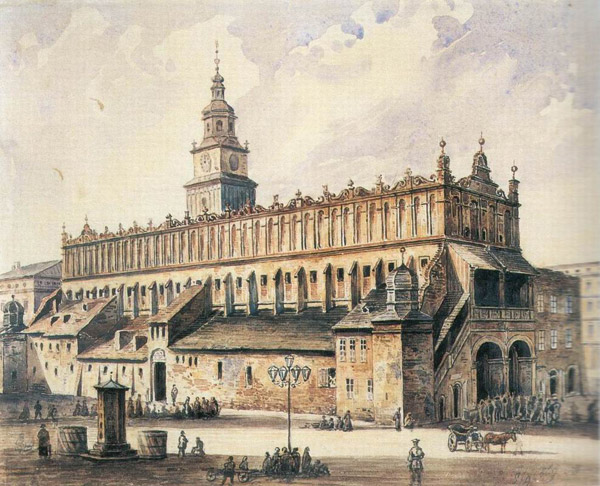

For centuries, the Cloth Hall, also known as the Sukiennice, has stood at the center of Kraków’s Rynek or main market square, welcoming merchants, students, kings, and travelers. Few buildings in Europe combine so much history, architectural beauty, and living tradition in one place. When you walk beneath its arches today, you’re experiencing a marketplace that has been operating for more than 700 years.

Cloth Hall is perhaps the most spectacular site in the town square, and St. Mary’s, the magnificent 800-year-old basilica, sits opposite it. The medieval town hall tower lies on the other side, providing great views and photo opportunities.

A Marketplace Born from Medieval Trade Routes

Kraków’s rise as a trading hub began early. The city sat at the crossroads of major medieval trading routes connecting Western Europe with the kingdoms of Ruthenia and the Black Sea, and the Baltic region with Hungary and the Mediterranean.

By the late 13th century, shortly after the city was rebuilt on a new grid plan under Magdeburg Law, a covered market hall stood in the center of the enormous Main Square. King Boleslaw the Bashful (1243-1279) is often credited with the design of the city square.

Merchants from England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, and the East passed through Kraków, making the town one of the major commercial stops in Central Europe. It is also believed that the counters’ exteriors provided lodging for traveling merchants.

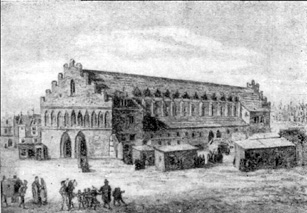

The Gothic Hall and Medieval Trade

The earliest Cloth Hall was a long Gothic-style building with market stalls lining a central passageway. Here, cloth merchants sold English broadcloth, Flemish linen, and local Polish textiles. The hall also served as a customs point where city officials inspected and taxed imported goods. Sukiennice, which literally means “little cloth shops”, quickly became the economic heart of Kraków.

But it wasn’t just cloth that moved through Kraków. Records from the Middle Ages show an astonishing variety of merchandise:

- Baltic amber

- Hungarian copper and lead

- Spices and leather goods from southern Europe

- Beeswax, salt from the Wieliczka mine, and metalwork

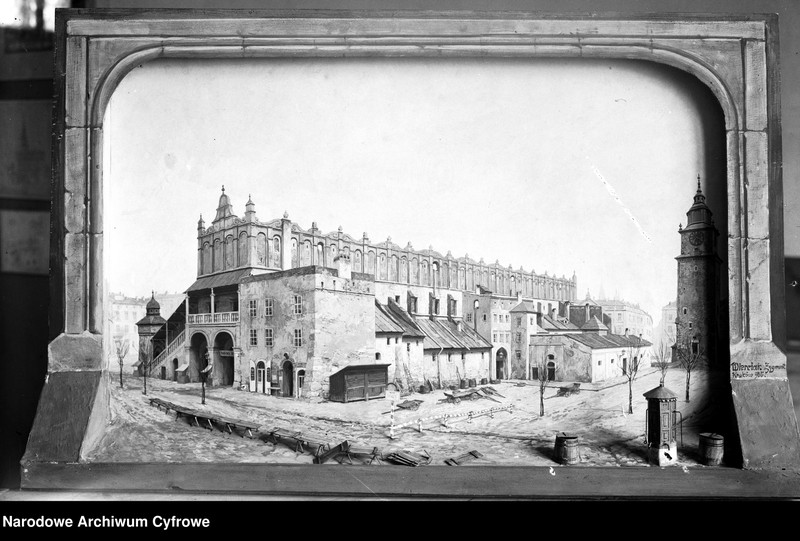

A devastating fire in 1555 allowed Kraków to rebuild the Cloth Hall in a more elegant style. Under the influence of Italian Renaissance artists and architects working throughout Poland, the Sukiennice gained a beautifully decorated attic parapet (a low wall that runs along the edge of the roof), with carved faces and ornate details. It was also given a grander, more harmonious façade and improved interior stalls.

This Renaissance reconstruction created the iconic appearance most visitors recognize today. It also reflected the prosperity of Kraków’s Golden Age, when the city was home to the royal court, wealthy guilds, and a thriving university.

From Prosperity to Decline

The fortunes of Kraków changed over the next few centuries. Wars, invasions, and shifts in European trade routes brought economic decline. By the 18th century, the Cloth Hall had grown shabby and outdated.

Everything changed in the 19th century. During the era of the Austrian Partition, when Poland no longer existed on the map, Kraków’s leaders set out to restore the Sukiennice as a symbol of Polish pride and cultural identity.

The Great 19th-Century Restoration

Between 1875 and 1879, Architect Tomasz Pryliński was contracted to redesign the exterior in a stylish Neo-Gothic manner. He created elegant arcades along both sides, and the interior was reorganized and repaired.

The upper floor became home to the National Museum’s Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art, the first national museum in Poland. This transformation solidified the Cloth Hall as both a cultural institution and a marketplace.

Sukiennice Today

A visit to Kraków wouldn’t be complete without stepping inside the Cloth Hall. Today, it remains a vibrant working marketplace and center for art and culture. The main hall still hosts rows of stalls, many run by artisans selling Polish folk art, amber jewelry, wooden carvings, embroidered linens, and other traditional crafts. In many ways, the Cloth Hall continues the commercial traditions of the medieval merchants who once worked here.

Upstairs, the National Museum displays some of Poland’s most important 19th-century paintings. Visitors can view dramatic historical scenes, romantic landscapes, and portraits that capture the spirit of the era.

A Window Underground

Beneath the building, the Rynek Underground Museum reveals the preserved foundations, stone roads, and merchant installations from medieval Kraków. It is one of the most fascinating archaeological museums in Europe. The entire town square was excavated from 1974 to the early 2000s.

The museum lets visitors walk through 800 years of Krakow’s history in a single underground corridor, revealing how the bustling market square evolved from a modest trading post to a Renaissance hub. You can see the foundations of the medieval town hall that burned down in 1498. The archaeologists found skeletal evidence of vampire burials that are on display.

More than anything, the Sukiennice brings together the threads of Kraków’s identity, trade, culture, architecture, and community into a single, beautifully preserved building.

If you are interested in the history of the Polish people, please check out my newly released book on Amazon: Our Polish Ancestors: The Cultural History of the Polish People from the Middle Ages to WWI. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0G2GN43RH